Table of Content

- Magmatic Processes

- Pneumatolytic and Hydrothermal Deposits

- Metasomatic Processes

- Sedimentary and Placer Deposits

- Weathering and Secondary Enrichment

Formation of Mineral Deposits

The term mineral deposit has been explained in the opening page of this chapter. A mineral deposit is simply a deposit of minerals, not necessarily commercially workable; its viability depends on fluctuating market prices. Thus, a mineral deposit considered unprofitable at one time may become economically extractable with an increase in its market price.

Magmatic Processes

Magma is the original source of most minerals. It is chemically reactive due to pressure, temperature, and the composition of various minerals. As it travels through adjacent rocks, it dissolves them, leading to the formation of new minerals. The constituent minerals, mostly rock-forming silicates and oxides, are deposited at various stages as the magma cools.

Minerals with similar fusion points tend to segregate and concentrate together, resulting in magmatic segregation. Important deposits of metallic oxides, such as magnetite and limonite, and sulphides like pyrrhotite and chalcopyrite, form through this process. Magmatic segregation can occur at different depths during the magma’s journey and at varying temperatures. Most ferromagnesium silicates and other oxides form at depth through magmatic segregation.

After magmatic segregation, the remaining magma is still fluid and contains various gases and vapors of volatile constituents. This process leads to the formation of pegmatites, which intrude pre-existing rocks. Economically significant mineral deposits such as feldspar, quartz, mica, and beryl are often found in pegmatites (e.g., in Giridih and Rajasthan).

Pneumatolytic and Hydrothermal Deposits

The formation of pegmatites leaves behind a highly fluid residual magma containing heated gases with strong chemical activity. These gases penetrate adjacent country rock and react with it to form mineral deposits known as pneumatolytic ore deposits. An example is cassiterite deposits.

During the final stage of magma consolidation, its aqueous solutions, which consist of heated waters of great chemical activity, deposit their mineral load. Because of their fluidity, these solutions can travel long distances from their parent source. The ore deposits formed by such aqueous but highly fluid solutions are called hydrothermal ore deposits. The term also includes deposits formed by descending surface waters that leach valuable constituents from existing rocks and precipitate them in cracks and fissures in the Earth’s crust.

Metasomatic Processes

Surface waters can penetrate deep into fissures and cracks, carrying dissolved minerals. The heat beneath the Earth’s surface renders these descending waters chemically active, sometimes replacing pre-existing rock minerals partially or completely, particle by particle. The structure of the original rock may remain unaltered. These ore deposits are called metasomatic ore deposits.

Metasomatism refers to the alteration of rocks due to the passage of heated waters from igneous sources. Some deposits of chlorite, serpentine, and chalcopyrite form this way. The metamorphism process can also generate enough heat and pressure to transform impure or low-grade ores into more valuable minerals. For example, some banded hematite formations in Salem and Tiruchirapalli districts have changed into banded magnetite-quartzite rocks.

Heat can also purify pre-existing minerals. Bituminous coal, for instance, can transform into anthracite near dykes and sills. Similarly, sillimanite (Al₂O₃, SiO₂) deposits in Assam and eastern Maharashtra and kyanite (Al₂O₃, SiO₂) form through metamorphism. Talc, a hydrated magnesium silicate, is another metamorphic product, found in magnesium-rich rocks like dolomite (e.g., near Jaipur in Rajasthan).

Sedimentary and Placer Deposits

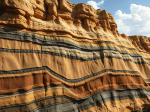

Some mineral deposits are of sedimentary origin. These deposits may form organically, as in coal formation, or chemically, as with some limestone and chalk deposits. Sedimentary deposits are always bedded and stratified.

Alluvial, detrital, or placer deposits form through the breakdown of parent rock and subsequent transportation of mineral particles by streams or wave action. The minerals accumulate where the velocity of water decreases, concentrating minerals according to their specific gravities. Examples include gold placers, where gold is often associated with magnetite and chromite, as well as deposits of platinum, tin, and wolfram.

Laterite deposits result from the leaching of soluble minerals, leaving behind valuable ores such as nickel or bauxite. These are typically surface deposits.

Weathering and Secondary Enrichment

Ore deposits exposed at the surface undergo weathering, which can alter their composition. The weathered upper part of the deposit is known as gossan, usually an oxidized zone that may transform into carbonates. For example, a vein of galena at depth may consist of cerussite (PbCO₃) in the gossan. Similarly, copper sulfide chalcopyrite (Cu₂S, Fe₂S₃) in a vein at depth can transform into malachite (CuCO₃·Cu(OH)₂) in the gossan (e.g., at Khetri in Rajasthan).

Mineral concentration occurs in the gossan as lighter and less stable minerals are washed away by percolating waters. As a result, rich mineral deposits of economic value often form a cap over low-grade ore.

Another process of mineral formation is evaporation. For example, salt forms by the evaporation of enclosed seawater, leading to the precipitation of dissolved minerals.

The formation of coal and related mineral deposits is explained in the next chapter.

Access the presentation from here. 03a Minerals – Google Slides

Leave a comment