- 1. Temperature

- 2. Pressure

- 3. Parent Rock Composition (Protolith)

- 4. Fluids (Water and Volatiles)

- 5. Time

- 6. Tectonic Forces

- Conclusion

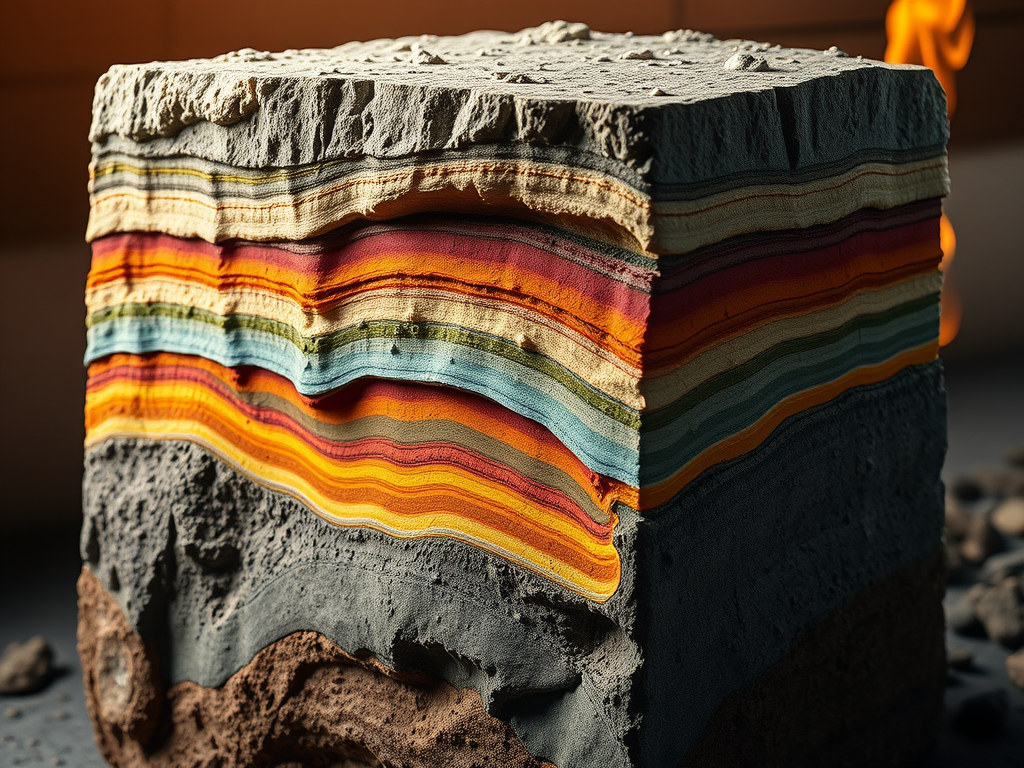

Metamorphism is the process by which pre-existing rocks undergo physical and chemical changes due to heat, pressure, and chemically active fluids. These changes occur while the rock remains solid, differentiating metamorphism from melting processes. Several key factors control metamorphic processes, influencing the mineral composition, texture, and structure of metamorphic rocks.

1. Temperature

Temperature is one of the most important factors in metamorphism as it directly affects the stability of minerals. When rocks are subjected to high temperatures, their minerals become unstable and begin to transform into new minerals that are stable under those conditions.

Sources of Heat:

- Geothermal Gradient: Temperature increases with depth in the Earth’s crust, typically around 25-30°C per kilometer.

- Intrusive Magma: Magma intrusions provide localized heat, leading to contact metamorphism.

- Frictional Heating: Tectonic activities, such as faulting, can generate heat through friction.

Effects of Temperature:

- Mineral Recrystallization: Minerals become larger and more stable under higher temperatures.

- Phase Changes: Some minerals change structure (e.g., quartz to coesite at high pressures).

- Dehydration & Decarbonation: Some minerals lose water (e.g., clay minerals transform into mica) or carbon dioxide (e.g., limestone turns into marble).

Temperature Ranges of Metamorphism:

- Low-grade metamorphism: ~150-450°C (e.g., formation of slate).

- Medium-grade metamorphism: ~450-650°C (e.g., schist formation).

- High-grade metamorphism: >650°C (e.g., gneiss formation and partial melting).

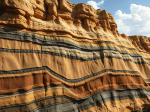

2. Pressure

Pressure affects rock structure, mineral stability, and texture. Pressure increases with depth and can be divided into two types:

Types of Pressure:

- Lithostatic (Confining) Pressure:

- Equal pressure from all directions due to deep burial.

- Causes compaction and volume reduction but does not create foliation.

- Common in burial metamorphism.

- Directed (Differential) Pressure:

- Unequal pressure, often from tectonic forces.

- Leads to deformation, foliation, and the alignment of minerals.

- Occurs in regional metamorphism, common in mountain-building zones.

Effects of Pressure:

- Increases Rock Density: Minerals become more compact, reducing pore spaces.

- Reorientation of Minerals: Causes platy minerals like mica to align, forming foliated textures.

- Phase Transformations: Some minerals form new, denser structures under high pressure (e.g., graphite transforms into diamond).

Pressure Conditions:

- Low-pressure metamorphism: Occurs at shallow depths.

- High-pressure metamorphism: Occurs at depths greater than 10 km, often in subduction zones.

3. Parent Rock Composition (Protolith)

The mineral composition of the original rock (protolith) determines the possible mineral assemblages in the metamorphic rock.

Examples of Parent Rock Influence:

- Shale → Slate → Schist → Gneiss (increasing metamorphism).

- Limestone → Marble (recrystallization of calcite).

- Basalt → Amphibolite (rich in mafic minerals like amphiboles).

Why is this important?

- Different parent rocks exposed to the same conditions can produce different metamorphic rocks.

- The chemical composition of the protolith limits the types of new minerals that can form.

4. Fluids (Water and Volatiles)

Fluids, especially water with dissolved ions, play a significant role in metamorphism by enhancing chemical reactions.

Sources of Metamorphic Fluids:

- Pore water trapped in sedimentary rocks.

- Water released from minerals during metamorphism (e.g., dehydration of clays).

- Hydrothermal fluids from magma intrusions.

Effects of Fluids:

- Facilitate Metasomatism: Fluids enable ion exchange, changing rock composition.

- Promote Recrystallization: Water speeds up mineral growth and stabilization.

- Create Veins and Mineral Deposits: Fluids transport and deposit minerals like quartz and gold.

Example:

- Greenschist Metamorphism: Water-rich conditions promote the formation of chlorite, epidote, and amphiboles.

5. Time

Metamorphic changes occur over long geological timescales, ranging from thousands to millions of years.

Why Time Matters:

- Longer exposure allows for more complete mineral transformations.

- Slow cooling leads to larger crystal growth, forming coarse-grained rocks like gneiss.

- Rapid changes (e.g., during faulting) can result in partially metamorphosed rocks like mylonite.

6. Tectonic Forces

Plate tectonics drive regional metamorphism by creating pressure, heat, and deformation.

Major Tectonic Settings for Metamorphism:

- Convergent Boundaries (e.g., Himalayas)

- High pressure and temperature conditions.

- Produces foliated rocks (e.g., schist, gneiss).

- Divergent Boundaries (e.g., Mid-Atlantic Ridge)

- Hydrothermal metamorphism from seawater circulation.

- Produces serpentinite and greenstone.

- Subduction Zones (e.g., Andes)

- High-pressure, low-temperature metamorphism.

- Produces blueschist and eclogite.

- Fault Zones

- Generates dynamic metamorphism (mylonites and cataclasites).

Conclusion

Metamorphic processes are driven by a combination of temperature, pressure, parent rock composition, fluids, time, and tectonic forces. These factors interact to produce a wide range of metamorphic rocks, each with unique mineral compositions and textures. Understanding these factors helps geologists interpret Earth’s history and the conditions under which different rocks formed.

keywords

Metamorphism, temperature, pressure, lithostatic pressure, differential pressure, fluids, volatiles, protolith, recrystallization, foliation, non-foliated, regional metamorphism, contact metamorphism, burial metamorphism, tectonic forces, schistosity, gneissic banding.

Leave a comment